A sense of unease

Salta lies in the far north of Argentina, a long way from Buenos Aires and the fertile plains of the pampas. Enveloped in an atmosphere soured by distance, passed over time and time again, the province is a stump of what was once the country’s strongest line of defense. A long time ago, the region knew prosperity in the years when it played the role of customs officer and dry port in the trade between the powerful Viceroyalties of Peru and the River Plate. The memory of those days, like a flower on a summer’s day, is deeply rooted in the minds of the local elite, despite the long, irreversible decay in the province’s fortunes. In fact, the political experience of its inhabitants today can be summed up in the words stagnation, cronyism and waiting.

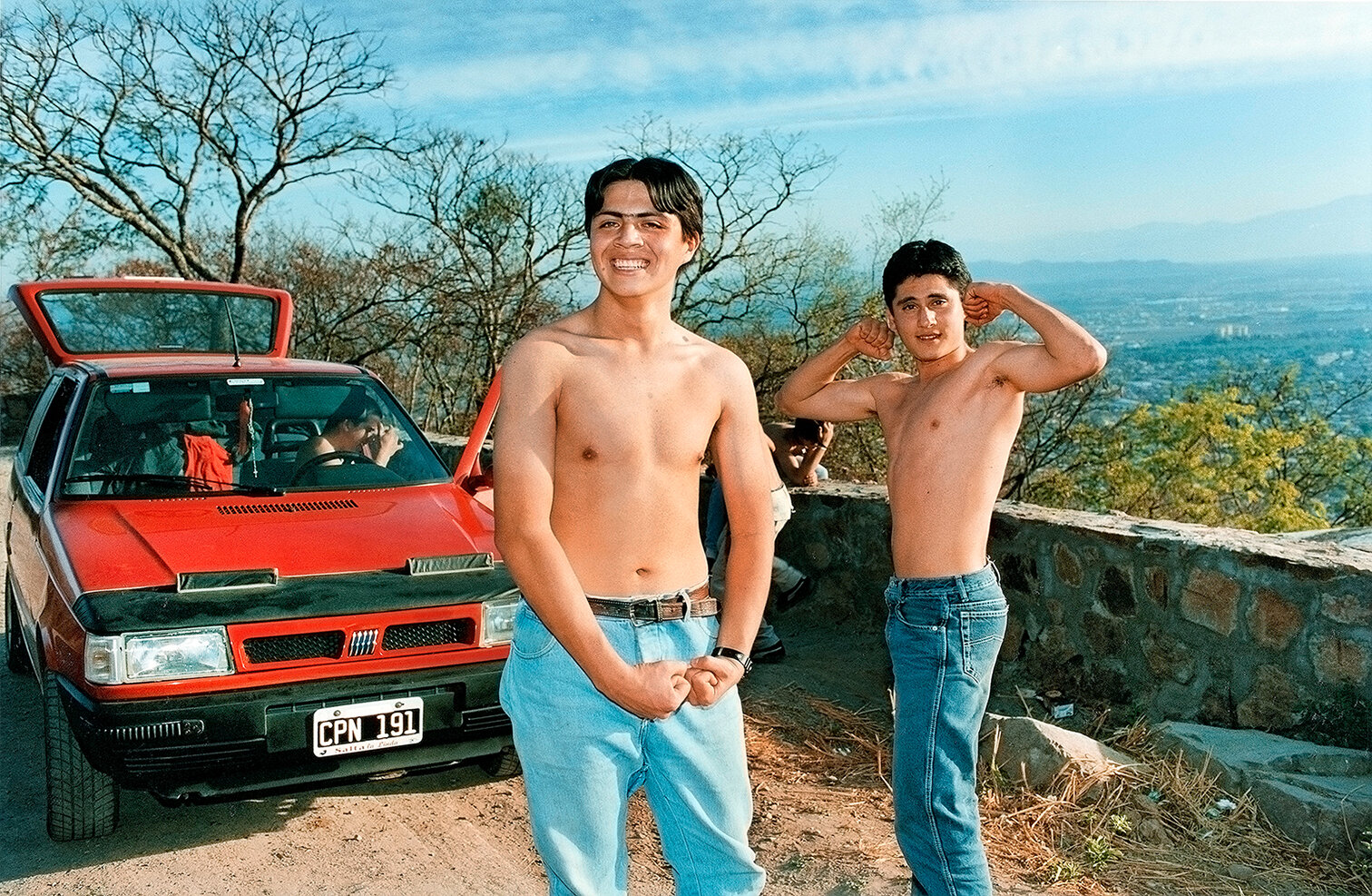

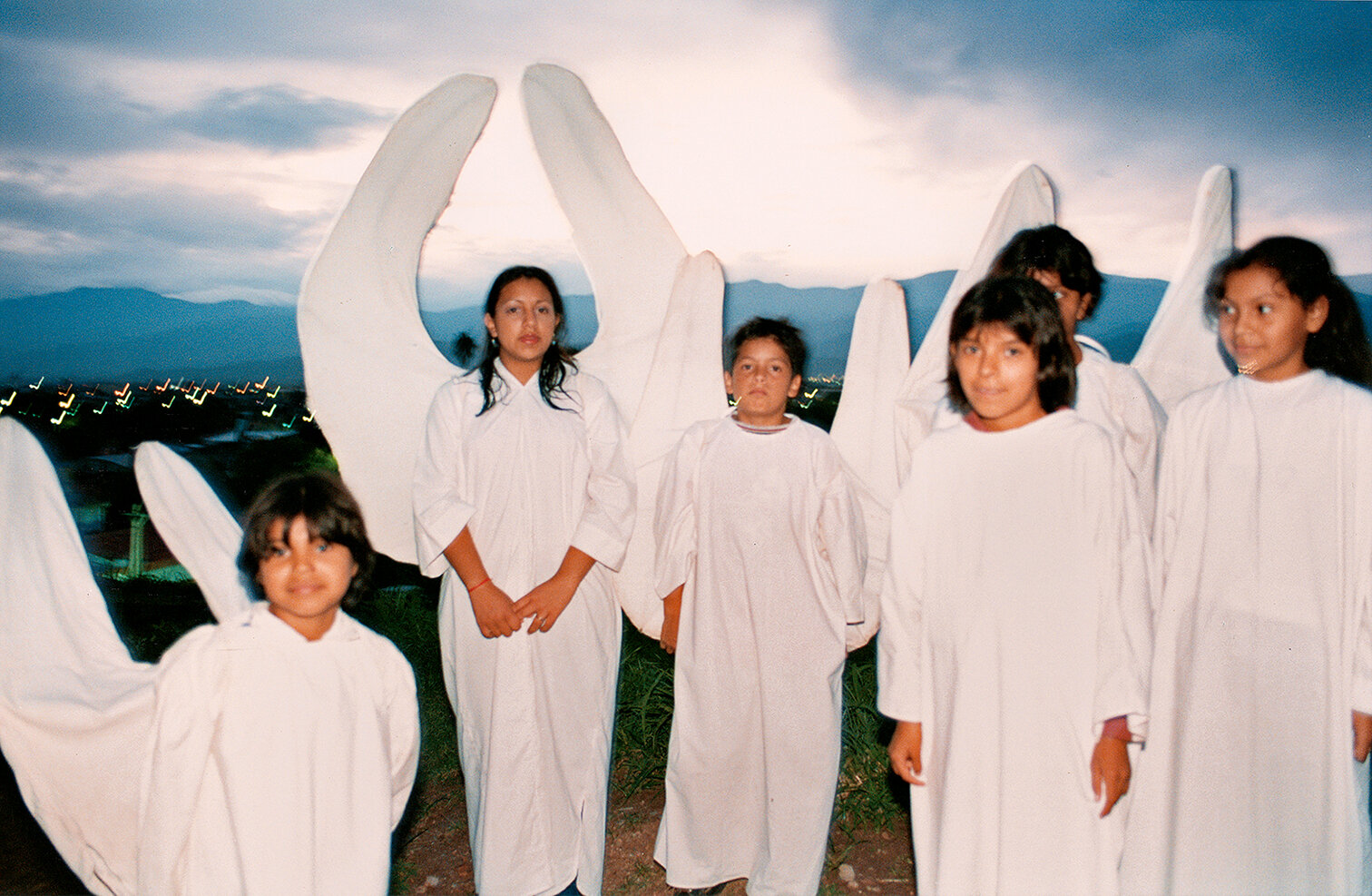

Florencia Blanco’s photographs taken in Salta seem at first sight to be bucolic frescoes or the record of quaint local customs. But this is far from the truth. There is a delicate violence imprinted on them, a barely perceptible sense of unease. Each picture has absorbed a singular measure of darkness from its subject-matter. Thus, in the jovial laughter of the students celebrating the first day of spring, there is a glimpse of the way in which they will have to bow before the implacable rules of social constraint. Their energy and spontaneity will seep away in centripetal domestic interiors where listless lives leach their vitality among heavy curtains, religious emblems, crepe covers, chandeliers and portraits of long-dead ancestors. We realize that the upbringing and education of many of the inhabitants of Salta begins and ends in these living rooms.

As if she had plumbed the depths of the public and private, nature and artificiality, festivity and loneliness with equal assiduity, Florencia Blanco has managed to comprehend the symbols, institutions and social cycles of this place. Both joy and tranquility have been documented, as too have the adoption of falsehoods and the forlornness of repeated rituals. At other times, the photographer is gripped by a fascination with certain locations which seem to be on the verge of extinction, because of their paper mache decorations, their unfashionable antique furniture and ancient billiard tables. The images that she rescues for posterity are in some way the end result of an act of mercy for the fate awaiting these places that people merely pass through.

Florencia Blanco has seen many things. She has seen Greek gods in men frolicking in the shallows of a river, funeral processions in the lines of people being evacuated from flooding, irredeemable anguish in the heavy air of living rooms, fantasy escape routes to the sea in a poster of paradise. There is water, a lot of it, in her pictures, a joyful murmur in a province of mountains and deserts, where the way to the sea has always been a major economic and political concern. While in one photo, a poster papering a café wall features beaches of impossibly paradisiacal beauty, in another, floodwaters swirl around the feet of six local lads at dusk.

There is an unsalvageable contrast between the city caught in its immobility and the placidity of nature which comes sharply into focus, between stiff social rituals and the refreshing relaxation afforded at the water’s edge. The mannequin of a bride in a shop window has more in common with the ornamental swan anchored in a garden lawn than with the indolent bodies blessed by streams and rivers. A lame dog and the stump of a tree stand out less in the city than in the woodland, as if the precariousness of existence were a consequence of civilization itself rather than of the difficulties which man has in his dealings with nature.

Florencia Blanco spent her childhood and teenage years in the city of Salta. Her photographs are an attempt to retrieve those visual memories sunk in time. The sensory development of a person during their formative years is still a mystery which defeats understanding. Children, like sponges, absorb the surrounding palette of colors just as much as they pick up tones of sadness and heartbreak, as well as the social rituals practiced by their elders. What we absorb marinates in the miasma of memory to return, unexpectedly, as a crepitation in our field of vision. If that process could be frozen for an instant, we might perhaps know why it is that photographers do what they do.

Christian Ferrer 2009